Contributing¶

Contributions are welcome, and they are greatly appreciated! Every little bit helps, and credit will always be given.

Fork the repo¶

Fork the repo into your personal profile. This will allow you to make changes and push them to your forked repo. When you’re ready, issue a pull request to the main repo.

Issues¶

Ideally, create an issue first. This will allow us to discuss the feature or bug fix you want to implement.

Pull Requests¶

Issue pull requests against the dev branch. Please make sure that your code

is covered by a test (see below).

Environment setup¶

- install poetry

- I prefer to set the default location of the virtual environment to the

project directory. You can set that as a global configuration for your

poetry installation like so:

poetry config virtualenvs.in-project true

-

git clone the repo

-

cd into the repo and issue the command

poetry install -

shell into the virtual environment with

poetry shell -

you can

pip install -e .to install the package in editable mode. This is useful if you want to test the cmd line interface as you make changes to the source code.

Tests are reproducible debugging tools!¶

There is a test suite provided with this package which is intended to give any future Calling Cards developers who might use this an easier way into the code. All code should be accessible from the current tests, and the current tests can be used to give some assurance that a new change doesn’t absolutely break any functionality.

However, the purpose of the tests is not to prove correctness. Rather, it is a record of the debugging that I have done. It makes the debugging reproducible!

The real benefit to me in the future, or you, if you have inherited this, is that you can use VScode to set breakpoints in the code. This means you don’t have to read my documentation or guess at what I was trying to do.

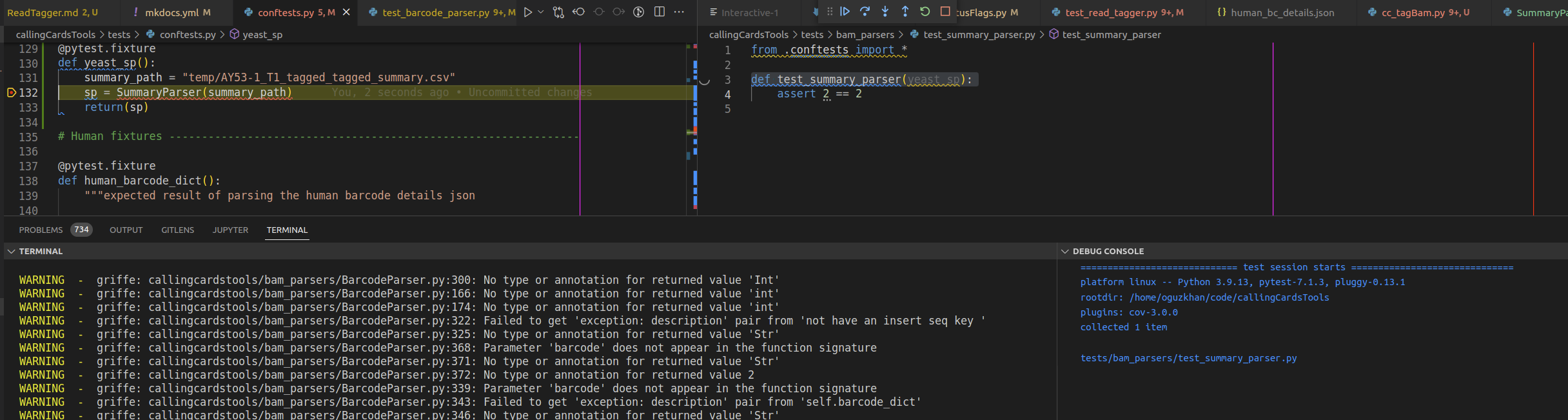

Here is an example:

What you’re seeing here is a a dummy test on the right. Notice that this test does nothing! it just says that 2 == 2. However, it is importing a fixture. A fixture is a test data object – in this case, it is a SummaryParser object that is loaded from test data that is provided in the package repository.

Notice that I have set a breakpoint on the SummaryParser() constructor. This

isn’t necessarily the most direct way or setting up this test, but it provides

an example of both a fixture, and proves that tests don’t need to actually

test anything at all to be useful.

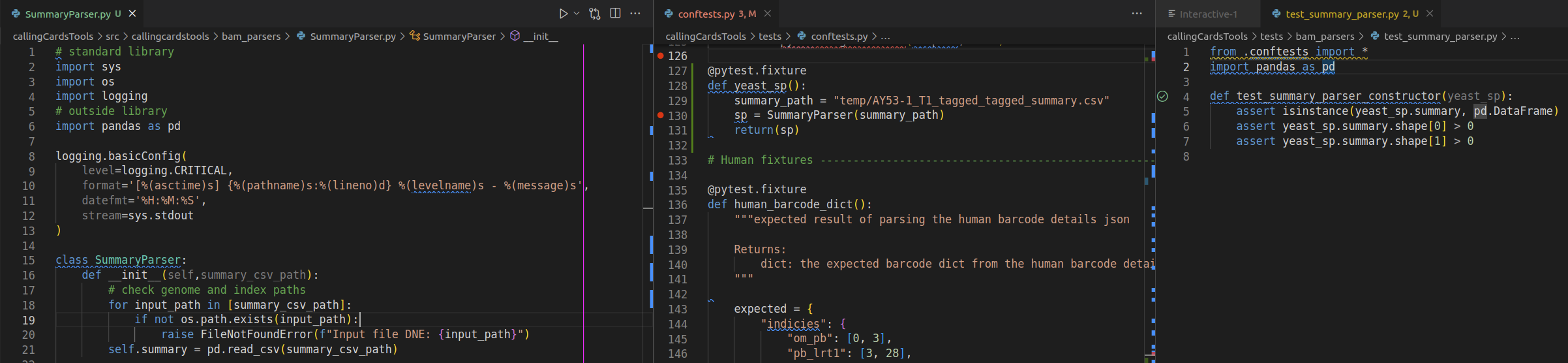

Why is this useful? Because now you can “step into” the SummaryParser constructor. When I wrote the constructor, I needed to make sure that it actually constructs. We do that by trying it out. Because I have provided this “test”, you can re-run that debugging process as many times as you wan to. You don’t need to read the documentation on what the SummaryParser() is supposed to do – just set a breakpoint and run the test – the execution will stop at the breakpoint and you’ll be in an interactive coding environment.

By doing this, as a developer, you can interatively improve the tests over time. As you debug, upon first writing or at any point in the future when you are debugging, just keep a record (that is the iteratively improved test). For example, maybe you write a more robust test of the constructor:

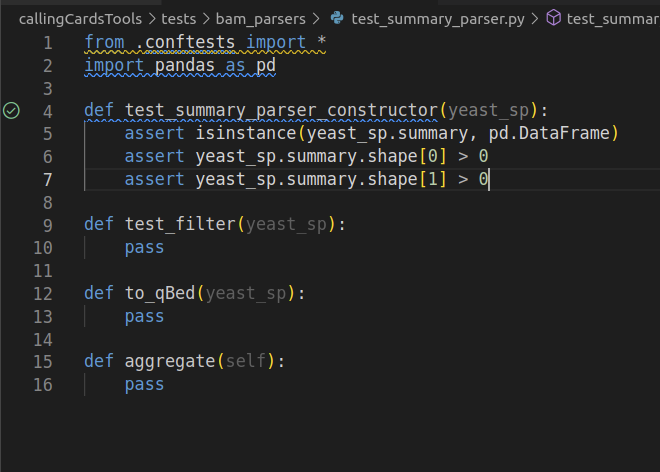

As you write the rest of the class, you’ll want to make sure that you’re including tests. At the very very least, provide the names of the tests:

If you’re good, then you’ll write this tests firsts, and then write the function. But most of us are mere mortals, and will write the functional code and the tests concurrently. You do this already, most likely – write and test in an interactive environment, and then copy/paste the working function into your production environment – the only difference between that, and using the testing framework, is that by using the testing framework, you’re providing a resource to yourself-in-the-future, and possibly other developers.